Late October 1955, rolling into Texas City on a Greyhound bus, this is what I saw:

On the distant skyline, a metropolis, huge, beckoning, a fantasy city. I mostly lived in books, so I compared it to Oz, the Emerald City, green and glowing. This town twinkled more like a Christmas tree, tiny orange lights running up the towering skyscrapers, an Amber City. And there were lighthouses.

“It’s so big,” I said, sleepy, never sure of my mother’s mental whereabouts, even though she sat right beside me.

“Not that big,” she said.

“But the buildings. And lighthouses?”

“What? Oh. The plants.” Her impatient tone closed the subject. Asked and answered.

In a symmetrical loop personal history often makes, my son at a young age told an interested adult that his dad worked in a flower shop. This was way off the mark, so I asked where he got that idea. “Daddy’s a plant manager,” he said. Perfect logic, and that remark took me right back to the night I saw Texas City for the first time. I would grow up, move away, and live in many cities, but I would call that little coastal town in Texas home for the rest of my life.

When I first saw it, I was almost 10 years old. I understood these plants weren’t organic things. No leaves. No green. It would sort itself out, I assumed, probably for the worse. That was my experience of life so far.

“Raymond works at Monsanto. Everyone works at the plants.” She closed her eyes, exhausted from an ordeal that began eight years ago and culminated in this cross-country flight from a marriage that never should have happened.

Uncle Raymond at Monsanto.

The flame-tongues topped smokestacks, not lighthouses. The amber lights framed miles of pipes, gauges, tanks, and other fittings of huge oil refineries. As we grew closer to town, the “buildings” in the distance morphed into skeletons, like an erector set. Raymond, who worked at Monsanto, was the husband of my mother’s sister Jackie.

Though I still glimpsed the lights in the distance, we were traveling through a much less impressive skyline now, and soon the air brakes sighed as the bus slowed and eased into a parking lot. So this is it, I thought.

Texas City. Blown to bits in 1947, blown away in 1961 (not for the first or last time), and smelling like a giant fart at all times due to the fumes from Monsanto, Union Carbide, Amoco, and the other refineries that provided a living for the town folk who remembered hard times. Since you never got used to going hungry, and you got used to the smell, most thought it was a good tradeoff. Explosions? Hurricanes? What did that matter weighed against three square meals a day, every day? And a home. And a car.

It was dark, and I thought it was Tuesday. My mother said we would be in Texas by Tuesday when we left, my mother, my sister and I. As soon as my father went out to do whatever he did during the day (it wasn’t work), we got in a cab, boarded a bus, and watched as New Castle, Pennsylvania, disappeared behind us. When my father discovered we were gone, he gave chase.

My mother would head to Texas City, he knew, because that’s where she grew up with her parents Ruby and Charley Benskin, and her sisters Jackie and Dorothy. My grandparents had moved “up the country” years before, but Aunt Jackie had settled in TC, and she was the strong one. We would go there because that’s where we could survive.

My father ambushed us somewhere in Kentucky or Indiana, sat us down in a dingy bus station diner, and did his charming best to convince my mother not to leave him. When it didn’t work, he turned mean, snatched my three-year-old sister, and left. After the kidnapping, we stayed in a cheap motel while my mother decided what to do, which was to push on, and here we were in a dark parking lot in Texas City.

As we waited our turn to disembark from the bus, I took advantage of the pause in forward motion to ask a question I’d been mulling over. Why did my father take my sister and leave me behind? It took courage to ask; I knew my mother wouldn’t like the question.

“She was easier to carry.” When confronted with thorny problems, my mother turned either vague or practical or both. Guess it was a weighty question to both of us, but not in the same way.

I adored my mother, but even so, at times she got on my nine-year-old nerves. I might as well have a butterfly for a mother. She was lovely, small, fragile, and she gave the false impression that her existence on earth was ephemeral. If I wasn’t careful, she would disappear in a puff of golden dust.

We got off the bus, and I saw a real estate office, a sign that said Bus Depot, and another sign – vertical – e above the l and so on – that said Ellis’. The “Restaurant” part behaved itself and stayed horizontal. My mother was canny about certain things, and she wanted to beat the other passengers to the phone booth. We headed to it, me trailing so close I slammed into her when she stopped. By the time the change trickled down the slot, there was a line behind us.

I heard only one side of the conversation. “Hello? Jackie? This is Hazel. I’m here.”

I could easily imagine what Jackie said: Hazel? Here? Here where?

“At the bus station.” She glanced at the sign. “Ellis’. Can you come get us? It’s just Becky and me. I’ll explain when I see you.”

No telling what shape she was in. She scraped together enough money to leave, had her youngest child grabbed along the way, and she had nothing but a high school education, good looks, and a sister she could count on. Few resources were available to women in those days, so this would have taken a super-human effort.

My mother backed out of the phone booth. “It’s Friday night. They were going to the football game, but they’re coming.”

I would believe it when I saw them. I was used to being misled by adults, and by now I knew it wasn’t even Tuesday. In Texas towns everyone knows where everyone is on Friday night. At the high school football game. Your kid doesn’t have to play. You don’t have to have a kid in school. It doesn’t matter if they haven’t won a game in 10 years.

But they did come, my Aunt Jackie, my Uncle Raymond, and my cousin Beverly. I had a cousin Ray, but he had gone to the game. Beverly, a curious 12-year-old, perhaps was not allowed to go, or maybe she thought our arrival was more interesting than football. She told me later when my aunt hung up and related our arrival, Uncle Raymond said, “Uh oh. Bet she’s left Dick.”

The next few comments probably went something like this:

Uncle Raymond: Well, thank God. But what will we do with them?

Aunt Jackie: Well, they’ll have to stay here for a while.

By the time we were in the car, my level of astonishment was hitting new peaks. It started with the non-lighthouses and ramped up over everything. The Morris’ enormous Oldsmobile. The volume of Beverly’s can-can slips. The mustard seed encased in glass on a gold chain around her neck. My possessions filled one small suitcase. I determined that I would get slips and a mustard seed as soon as possible. Somehow.

My cousin Ray, Uncle Raymond, Beverly, and the “Big Oldsmobile.” It was light blue and white. Very classy.

Looking out the car window, I was impressed. Everything was so … orderly. No twists and turns, no hills, not even trees to speak of, no Pennsylvania dusting of early snow. Just streets crossing each other on an axis. No frills. The buildings might have been made from giant shoe boxes in slightly varied sizes. In 1955 it would have been hard to name anything in Texas City that was pretty, except the sky, but even the proudest residents credited God and not the municipality for that. Still, this plainness struck me as perfect. Up until then, nothing in my life approached orderly. What a relief.

Inside the Morris home on 21st Avenue, things were pretty. Cared for. It was wonderful. I was installed in Beverly’s room where the wonders continued. I admired her orange and black banners, cut-outs, and book covers, and I remarked on her enthusiasm for Halloween, which was only days away. She looked at me like I must be out of my mind.

“Oh.” She laughed. “Orange and black. That’s the high school colors. In Texas City it’s always Halloween!”

I learned how true Bev’s statement was, and as the kids say today, in a good way. A lot of words describe my home town in the 50s and 60s. Wacky. Weird. Wonderful. Petty. Safe. Generous. Interesting. Boring. Just like Halloween.

I don’t know a lot about the machinations of the next months. The Morris family supported us; I don’t know where my mother would have gotten any money otherwise. She worked for a time at the Singer store down on Sixth Street. Everything was down on Sixth Street – I heard that all the time. Where’s the drugstore? Down on Sixth Street. Where’s the movie? Down on Sixth Street.

And Down on Sixth Street the Butterfly got fired because she couldn’t keep her mind on her work for worrying about my stolen baby sister.

At the time I was weirdly in sync with my mother. One evening Bev and I were Christmas shopping (Down on Sixth Street). I was intoxicated by the bins of colorful options in Rock’s Variety Store, but even so, I suddenly had a vision of my mother falling in front of a car. She was blocks away at Penny’s, but I saw it in my head and felt her sickening fear. The car stopped, and she was unhurt, but when they told me about it, I didn’t say a word. They wouldn’t have believed me anyway, and I had enough to figure out, mostly the people I didn’t know but found myself living with.

I loved my aunt and her husband Raymond immediately. To this day, when I hear the word “decent,” they come to mind. Also kind. My cousin Beverly laughed a lot, and I liked that. Also, she was a girl, so we had that in common.

My cousin Ray, on the other hand, was as exotic as a purple giraffe, and he scared the crap out of me for no reason except he was the first teenage boy I ever met. He had good manners and a kind heart, so he did his best to tolerate the invasion of the Butterfly and her spawn, but he was tall, good-looking, had a crew cut, and could drive a car. People called him on the phone. I never saw anything like it. He was 17. I was awed.

As for Beverly, she tolerated me with grace most of the time, especially considering I lived not only in her house, but in her room. One night after lights out, my tossing about like a mangy cat got to her. In a snit, she jumped out of bed and rummaged in her combination desk/dressing table. (An amazing piece of furniture – you lifted the lid and there were cubbie holes in the cavity and a mirror on the back of the lid – fantastic.) Among the pink lipsticks and glittery bits, she found what she was looking for – a piece of colored chalk. She drew a line down the middle of the bed, which horrified me. Defacing anything was a mortal sin in the 50s. Then she threatened me with death if I crossed the line during the night.

She leaned in and lowered her voice. “I was here when the disaster happened, you know.”

Bev’s encounter with the grim reaper (she used that term) happened while she was picking buttercups in Snug Harbor (a neighborhood, not a harbor). She was little more than a baby on April 16, 1947, when the S.S. Grandcamp exploded in Texas City harbor, and the force of the blast (five miles away) flattened her. All hell broke loose that day; 145 people died at Monsanto alone, but Uncle Raymond worked for Carbide then, so he was OK. “Hundreds of others were killed, too,” my cousin said, “all over town. Bodies everywhere.”

I was horrified, impressed, astonished, amazed, and after that, I woke up every morning clinging to my side of the bed.

The last member of the Morris household was Teddy the parakeet, who was allowed out of his cage to fly around at will. I had never imagined such a pet, and I wondered about bird ca-ca. Aunt Jackie kept a clean house, so where did it go?

One morning Teddy lined up his landing with the back of my mother’s head and swooped in from behind. She didn’t see him coming, and the tiny explosion of tangled curls and bird talons caused her to collapse. When it was over, she was on the floor, her cup was shattered, there was coffee on all nearby surfaces, and Teddy, in a panic, got loose and delivered a load of ca-ca pretty much everywhere. Chaos.

The colored girl was called in, another unheard-of amazement. The Morris’ had a colored girl who came sometimes, and I was to see her and my aunt, both on their knees scrubbing the floor. You called them “colored” to be polite, and you got your money’s worth by working as hard as they did. There was no bird ca-ca left when they were done, and I learned something. If you want to inspire people to work hard, work hard yourself.

Against all this newness a fresh dread arose. I heard conversations about my mother’s plans to return to Pennsylvania to retrieve my sister, and after the first of the year, it happened. She left on a train, and I thought I would never see her again. Neither Aunt Jackie’s kind reassurances nor Uncle Raymond’s offers of Coca Cola could convince me she would come back. She did, and with my baby sister. Poor Morris family. Now we were multiplying.

The return of my mother was a miracle. I didn’t think my father would part with Tish, and I didn’t think my mother would come back for me. When my father snatched my sister and left me behind, I was forever consigned to the world of the less desirable, but at least with the return of my sister, my mother became functional. She found a job, and she kept it.

The fact that my aunt worked outside the home was controversial – it was the era of “my wife doesn’t have to work” – but they had a brand new home with a mortgage, a couple of half-grown kids, and my uncle’s pay as a pipe fitter, though good for the times, didn’t cover all their dreams. Ray for sure would go to college and Beverly, too, if she didn’t get married first. That’s how folks thought then, especially blue-collar folks, and that was Texas City. A beautiful, blue-collar town, through and through. And although Aunt Jackie spoke softly and was as pretty as my mother, my aunt didn’t flit around, not ever. When her family needed extra money, she got a job.

Furthermore, her job led to my mother’s job. Aunt Jackie learned that a doctor in the same building where she worked needed a receptionist. My aunt put forth my mother’s name, and Dr. Leonti hired her. We moved into a garage apartment belonging to the Widow Wagner on Fourth Avenue.

The best thing about it was the view across the alley to St Mary’s Catholic Church, a mission-style mystery to the Protestants, and a pretty exception to the shoe-box architecture in town.

By then I was 10 years old, and I was officially a Texas Citian. I was home.

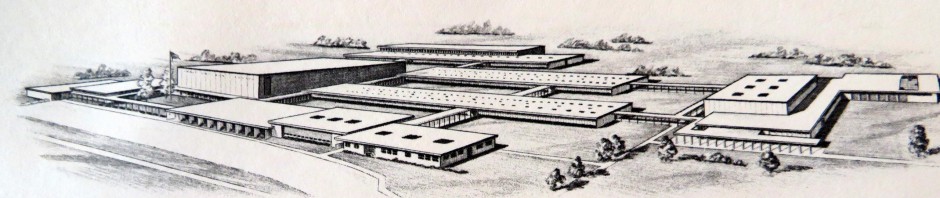

NEXT: The Phantom of the Fourth Grade, Roosevelt-Wilson Elementary School

Wonderful story! I thought I was the only one who didn’t have enough to eat.

Looking forward the next episode.

Linda

LikeLike

I’m learning what I should have known all along. I’m not the only one . . . Thank you, Linda, for your kind words.

LikeLike

I found this article very interesting being the son of Tish

LikeLike

I’m glad you know this story now, Jason. I’m sure your mother didn’t remember it, but things that happen when we’re very young, even when we don’t remember, have a lasting effect. I’m no expert, but that’s what I think, anyway.

LikeLike

My mother came toTC as an employee of Dr. Jarrell, whose wife was from Galveston. After the war, my dad was working construction at Carbide. As luck would have it, my married parents, with mom living in Somerville as a nanny for the Jerell’s and my dad living and working in TC, got to finally be together in one city. We also lived in Snug Harbor on 11th street, but did not know your uncle and aunt.

LikeLike

I remember you lived in Snug Harbor. We dropped you off (or picked you up) many times on those water-skiing Sundays with “the gang.” My aunt and her family moved to 21st Avenue about 1953 or 54. When I went back to TC with Bev a few years ago, we went by their Snug Harbor house, and I thought about you. Interesting about Dr. Jarrell. Do you remember that his wife taught French at TCHS?

LikeLike

I enjoyed this story so much. Thanks for writing this with such clarity and emotion. You’ve placed me at the scene with you. You’re a very good writer and I’m curious if you attended classes on creative writing?

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed the blog, and thanks for asking about writing. It’s like lots of things — 90 per cent hard work and 10 per cent talent. I’ve always written things down, but when I lived in Atlanta I enrolled in an adult education creative writing class. After the class was finished, the wonderful teacher (Prof. Jane Hill) invited six or seven of us to be in a special group, and we worked with her for several years. She had a way of taking the skills we had and showing us how to use them. I’m grateful to her, and to those other great writers. We shared our work, learned both to critique honestly but not hurtfully, and how to make the most of any natural talent we had.

LikeLike